What Kind of Jewelry Clothes and Art Work Do Christian Goths Use

Black and white photography of a woman dressed in goth manner

Goth is a subculture that began in the United Kingdom during the early 1980s. It was developed by fans of Gothic rock, an adjunct of the post-punk music genre. The name Goth was derived direct from the genre. Notable post-punk artists who presaged the Gothic rock genre and helped develop and shape the subculture include: Siouxsie and the Banshees, Bauhaus, the Cure, and Joy Segmentation.

The goth subculture has survived much longer than others of the same era, and has continued to diversify and spread throughout the globe. Its imagery and cultural proclivities indicate influences from 19th-century Gothic fiction and from horror films. The scene is centered on music festivals, nightclubs, and organized meetings, especially in Western Europe. The subculture has associated tastes in music, aesthetics, and fashion.

The music preferred by goths includes a number of styles such as gothic stone, death rock, common cold wave, nighttime wave, and ethereal moving ridge.[one] Styles of clothes within the subculture depict on punk, new moving ridge, and New Romantic way.[2] It also draws from the fashion of earlier periods such as the Victorian, Edwardian, and Belle Époque eras. The style almost often includes dark (usually solid blackness) attire, night makeup, and black hair. The subculture has continued to describe interest from a big audience decades afterwards its emergence.

Music [edit]

Origins and development [edit]

The term gothic rock was coined past music critic John Stickney in 1967 to describe a meeting he had with Jim Morrison in a dimly lit wine-cellar, which he chosen "the perfect room to honor the Gothic rock of the Doors".[3] That same year, the Velvet Surreptitious vocal "All Tomorrow'south Parties" created a kind of "mesmerizing gothic-rock masterpiece" according to music historian Kurt Loder.[4] In the late 1970s, the gothic adjective was used to describe the atmosphere of postal service-punk bands like Siouxsie and the Banshees, Magazine, and Joy Division. In a live review about a Siouxsie and the Banshees' concert in July 1978, critic Nick Kent wrote that, concerning their music, "[P]arallels and comparisons can now be drawn with gothic stone architects like the Doors and, certainly, early Velvet Clandestine".[v] In March 1979, in his review of Magazine's second anthology Secondhand Daylight, Kent noted that there was "a new ascetic sense of authority" in the music, with a "dank neo-Gothic sound".[6] Later that twelvemonth, the term was also used by Joy Division's manager, Tony Wilson on 15 September in an interview for the BBC Television plan's Something Else. Wilson described Joy Partitioning as "gothic" compared to the pop mainstream, right before a live performance of the band.[vii] The term was later applied to "newer bands such as Bauhaus who had arrived in the wake of Joy Division and Siouxsie and the Banshees".[8] Bauhaus's first single issued in 1979, "Bela Lugosi's Dead", is by and large credited as the starting point of the gothic stone genre.[9]

In 1979, Sounds described Joy Division equally "Gothic" and "theatrical".[10] In February 1980, Melody Maker qualified the same band equally "masters of this Gothic gloom".[11] Critic Jon Savage would after say that their vocalizer Ian Curtis wrote "the definitive Northern Gothic statement".[12] However, it was not until the early 1980s that gothic rock became a coherent music subgenre within post-punk, and that followers of these bands started to come together as a distinctly recognizable movement. They may have taken the "goth" mantle from a 1981 commodity published in UK stone weekly Sounds: "The face of Punk Gothique",[13] written past Steve Keaton. In a text nigh the audience of UK Disuse, Keaton asked: "Could this exist the coming of Punk Gothique? With Bauhaus flying in on like wings could it exist the next big thing?"[thirteen] The F Society night in Leeds in Northern England, which had opened in 1977 firstly as a punk order, became instrumental to the development of the goth subculture in the 1980s.[14] In July 1982, the opening of the Batcave[fifteen] in London'due south Soho provided a prominent meeting point for the emerging scene, which would be briefly labelled "positive punk" by the NME in a special issue with a front cover in early on 1983.[xvi] The term Batcaver was then used to depict quondam-school goths.

Bauhaus—Alive in concert, 3 February 2006

Outside the British scene, deathrock developed in California during the late 1970s and early 1980s as a distinct branch of American punk rock, with acts such every bit Christian Expiry and 45 Grave at the forefront.[17]

Gothic genre [edit]

The bands that divers and embraced the gothic rock genre included Bauhaus,[18] early on Adam and the Ants,[nineteen] the Cure,[xx] the Birthday Political party,[21] Southern Death Cult, Specimen, Sexual activity Gang Children, UK Decay, Virgin Prunes, Killing Joke, and the Damned.[22] Near the summit of this outset generation of the gothic scene in 1983, The Face 'due south Paul Rambali recalled that there were "several stiff Gothic characteristics" in the music of Joy Division.[23] In 1984, Joy Division's bassist Peter Hook named Play Expressionless every bit one of their heirs: "If you listen to a band similar Play Dead, who I really like, Joy Division played the same stuff that Play Dead are playing. They're similar."[24]

By the mid-1980s, bands began proliferating and became increasingly popular, including the Sisters of Mercy, the Mission, Conflicting Sex Fiend, the March Violets, Xmal Deutschland, the Membranes, and Fields of the Nephilim. Record labels like Manufacturing plant, 4AD and Beggars Feast released much of this music in Europe, and through a vibrant import music market in the United states of america, the subculture grew, especially in New York and Los Angeles, California, where many nightclubs featured "gothic/industrial" nights. The popularity of 4AD bands resulted in the cosmos of a similar Usa label, Projekt, which produces what was colloquially termed ethereal moving ridge, a subgenre of dark wave music.

The 1990s saw further growth for some 1980s bands and the emergence of many new acts, likewise every bit new goth-axial U.S. record labels such as Cleopatra Records, amongst others. Co-ordinate to Dave Simpson of The Guardian, "[I]n the 90s, goths all but disappeared as dance music became the dominant youth cult".[25] As a result, the goth "movement went underground and mistaken for cyber goth, Shock stone, Industrial metal, Gothic metal, Medieval folk metallic and the latest subgenre, horror punk".[25] Marilyn Manson was seen as a "goth-shock icon" by Spin.[26]

Fine art, historical and cultural influences [edit]

The Goth subculture of the 1980s drew inspiration from a diversity of sources. Some of them were modern or contemporary, others were centuries-onetime or aboriginal. Michael Bibby and Lauren M. E. Goodlad liken the subculture to a bricolage.[27] Amid the music-subcultures that influenced information technology were Punk, New wave, and Glam.[27] Just it besides drew inspiration from B-movies, Gothic literature, horror films, vampire cults and traditional mythology. Among the mythologies that proved influential in Goth were Celtic mythology, Christian mythology, Egyptian mythology, and various traditions of Paganism.[27]

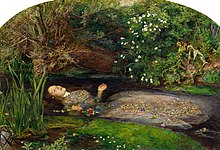

The figures that the move counted amid its historic canon of ancestors were as various. They included the Pre-Raphaelite Alliance, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844‒1900), Comte de Lautréamont (1846‒1870), Salvador Dalí (1904‒1989) and Jean-Paul Sartre (1905‒1980).[27] Writers that accept had a significant influence on the movement also represent a diverse canon. They include Ann Radcliffe (1764‒1823), John William Polidori (1795‒1821), Edgar Allan Poe (1809‒1849), Sheridan Le Fanu (1814-1873), Bram Stoker (1847‒1912), Oscar Wilde (1854‒1900), H. P. Lovecraft (1890‒1937), Anne Rice (1941‒2021), William Gibson (1948‒), Ian McEwan (1948‒), Tempest Constantine (1956‒2021), and Poppy Z. Brite (1967‒).[27]

18th and 19th centuries [edit]

Gothic literature is a genre of fiction that combines romance and dark elements to produce mystery, suspense, terror, horror and the supernatural. According to David H. Richter, settings were framed to accept place at "...ruinous castles, gloomy churchyards, claustrophobic monasteries, and lone mountain roads". Typical characters consisted of the cruel parent, sinister priest, mettlesome victor, and the helpless heroine, along with supernatural figures such as demons, vampires, ghosts, and monsters. Often, the plot focused on characters ill-fated, internally conflicted, and innocently victimized past harassing malicious figures. In addition to the dismal plot focuses, the literary tradition of the gothic was to also focus on individual characters that were gradually going insane.[28]

English language writer Horace Walpole, with his 1764 novel The Castle of Otranto is one of the first writers who explored this genre. The American Revolutionary War-era "American Gothic" story of the Headless Horseman, immortalized in "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" (published in 1820) by Washington Irving, marked the arrival in the New World of dark, romantic storytelling. The tale was composed by Irving while he was living in England, and was based on popular tales told past colonial Dutch settlers of the Hudson Valley, New York. The story would be adjusted to film in 1922,[29] in 1949 as the animated The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad,[30] and again in 1999.[31]

Throughout the evolution of the goth subculture, archetype Romantic, Gothic and horror literature has played a significant role. Due east. T. A. Hoffmann (1776–1822), Edgar Allan Poe[32] (1809–1849), Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867),[32] H. P. Lovecraft (1890–1937), and other tragic and Romantic writers have go as allegorical of the subculture[33] as the use of dark eyeliner or dressing in blackness. Baudelaire, in fact, in his preface to Les Fleurs du mal (Flowers of Evil) penned lines that could serve every bit a sort of goth malediction:[34]

C'est 50'Ennui! —50'œil chargé d'un pleur involontaire,

Il rêve d'échafauds en fumant son houka.

Tu le connais, lecteur, ce monstre délicat,

—Hypocrite lecteur,—monday semblable,—mon frère!Information technology is Boredom! — an eye brimming with an involuntary tear,

He dreams of the gallows while smoking his water-pipage.

You know him, reader, this delicate monster,

—Hypocrite reader,—my twin,—my brother!

Visual fine art influences [edit]

The gothic subculture has influenced unlike artists—not only musicians—but also painters and photographers. In item their work is based on mystic, morbid and romantic motifs. In photography and painting the spectrum varies from erotic artwork to romantic images of vampires or ghosts. There is a marked preference for dark colours and sentiments, similar to Gothic fiction. At the end of the 19th century, painters similar John Everett Millais and John Ruskin invented a new kind of Gothic.[35]

20th century influences [edit]

| | This section needs expansion. Y'all tin can help by adding to it. (October 2017) |

Some people credit Jalacy "Screamin' Jay" Hawkins, perhaps best known for his 1956 song "I Put A Spell on Y'all," every bit a foundation of modernistic goth style and music.[36] Some people credit the ring Bauhaus' starting time single "Bela Lugosi's Dead", released in August 1979, with the start of goth subculture.[ix]

21st century [edit]

| | This section needs expansion. Y'all tin can help past adding to it. (October 2017) |

The British sitcom The Information technology Crowd featured a recurring goth graphic symbol named Richmond Avenal, played by Noel Fielding. Fielding said in an interview that he himself had been a goth at age xv and that he had a serial of goth girlfriends. This was the first time he dabbled in makeup. Fielding said that he loved his girlfriends dressing him upward.[37]

Characteristics of the scene [edit]

Icons [edit]

Notable examples of goth icons include several bandleaders: Siouxsie Sioux, of Siouxsie and the Banshees; Robert Smith, of the Cure; Peter Spud, of Bauhaus; Rozz Williams, of Christian Death; Olli Wisdom, leader of the band Specimen[38] and keyboardist Jonathan Melton aka Jonny Slut, who evolved the Batcave style.[39] Some members of Bauhaus were, themselves, fine fine art students or active artists. Nick Cave was dubbed equally "the thousand lord of gothic lushness".[40]

Style [edit]

Influences [edit]

One female person office model is Theda Bara, the 1910s femme fatale known for her dark eyeshadow.[41] [42] In 1977, Karl Lagerfeld hosted the Soirée Moratoire Noir party, specifying "tenue tragique noire absolument obligatoire" (black tragic dress absolutely required).[43] The event included elements associated with leatherman style.[43]

Siouxsie Sioux was particularly influential on the dress style of the Gothic stone scene; Paul Morley of NME described Siouxsie and the Banshees' 1980 gig at Futurama: "[Siouxsie was] modeling her newest outfit, the one that volition influence how all the girls dress over the side by side few months. Most half the girls at Leeds had used Sioux equally a basis for their appearance, pilus to ankle".[44] Robert Smith,[45] Musidora, Bela Lugosi,[46] Bettie Page, Vampira, Morticia Addams,[42] Nico, Rozz Williams, David Bowie,[47] Lux Interior[47] and Dave Vanian[48] are also style icons.

The 1980s established designers such every bit Drew Bernstein of Lip Service, and the 1990s saw a surge of US-based gothic fashion designers, many of whom go on to evolve the way to the present day. Mode magazines such as Gothic Beauty have given repeat features to a select few gothic way designers who began their labels in the 1990s, such as Kambriel, Rose Mortem, and Tyler Ondine of Heavy Crimson.[49]

Styling [edit]

A male trad-Goth wearing Batcave style article of clothing.

Gothic fashion is marked past clearly night, blowsy and homogeneous features. It is stereotyped as eerie, mysterious, complex and exotic.[50] A dark, sometimes morbid way and style of dress,[47] typical gothic manner includes colored black hair and black period-styled clothing.[47] Both male and female goths tin can wear nighttime eyeliner and dark fingernail shine, nigh especially black. Styles are oftentimes borrowed from punk fashion and—more currently—from the Victorian and Elizabethan periods.[47] It also often expresses pagan, occult or other religious imagery.[51] Gothic fashion and styling may also characteristic silver jewelry and piercings.

A gothic model pictured in June 2008

Ted Polhemus described goth fashion as a "profusion of black velvets, lace, fishnets and leather tinged with ruddy or purple, accessorized with tightly laced corsets, gloves, precarious stilettos and silverish jewelry depicting religious or occult themes".[52] Of the male person "goth look", goth historian Pete Scathe draws a distinction between the Sid Fell archetype of blackness spiky hair and black leather jacket in contrast to the gender ambiguous guys wearing makeup. The kickoff is the early goth gig-going await, which was essentially punk, whereas the 2nd is what evolved into the Batcave nightclub look. Early on goth gigs were oftentimes very hectic affairs, and the audience dressed accordingly.

In contrast to the LARP-based Victorian and Elizabethan pomposity of the 2000s, the more Romantic side of 1980s trad-goth—mainly represented past women—was characterized by new wave/postal service-punk-oriented hairstyles (both long and curt, partly shaved and teased) and street-compliant clothing, including blackness frill blouses, midi dresses or tea-length skirts, and floral lace tights, Dr. Martens, spike heels (pumps), and pointed toe buckle boots (winklepickers), sometimes supplemented with accessories such as bracelets, chokers and bib necklaces. This mode, retroactively referred to as Ethergoth, took its inspiration from Siouxsie Sioux and mid-1980s protagonists from the 4AD roster like Liz Fraser and Lisa Gerrard.[53]

The New York Times noted: "The costumes and ornaments are a glamorous cover for the genre's somber themes. In the earth of Goth, nature itself lurks as a malign protagonist, causing mankind to rot, rivers to inundation, monuments to crumble and women to turn into slatterns, their hair streaming and lipstick askew".[fifty]

Cintra Wilson declares that the origins of the nighttime romantic style are constitute in the "Victorian cult of mourning."[54] Valerie Steele is an expert in the history of the style.[54]

Reciprocity [edit]

Goth fashion has a reciprocal human relationship with the fashion world. In the later part of the first decade of the 21st century, designers such as Alexander McQueen,[54] [55] [56] Anna Sui,[57] Rick Owens,[56] Gareth Pugh, Ann Demeulemeester, Philipp Plein, Hedi Slimane, John Richmond, John Galliano,[54] [55] [56] Olivier Theyskens[56] [58] and Yohji Yamamoto[56] brought elements of goth to runways.[54] This was described as "Haute Goth" by Cintra Wilson in the New York Times.[54]

Thierry Mugler, Claude Montana, Jean Paul Gaultier[fifty] and Christian Lacroix accept besides been associated with the fashion trend.[54] [55] In Spring 2004, Riccardo Tisci, Jean Paul Gaultier, Raf Simons and Stefano Pilati dressed their models as "glamorous ghouls dressed in form-plumbing fixtures suits and coal-tinted cocktail dresses".[58] Swedish designer Helena Horstedt and jewelry artist Hanna Hedman also exercise a goth aesthetic.[59]

Critique [edit]

Gothic styling oft goes manus in mitt with aesthetics, actuality and expression, and is mostly considered to be an "artistical concept". Dress are often self-designed.

In recent times, particularly in the course of commercialization of parts of the Goth subculture, many not-involved people developed an involvement in night fashion styles and started to adopt elements of Goth clothing (primarily mass-produced goods from malls) without being continued to subcultural nuts: goth music and the history of the subculture, for example. Within the Goth motion they accept been regularly described as "poseurs" or "mallgoths". [60]

Films [edit]

Film affiche for The Hunger, an influence in the early days of the goth subculture[61]

Some of the early on gothic stone and deathrock artists adopted traditional horror film images and drew on horror film soundtracks for inspiration. Their audiences responded by adopting appropriate dress and props. Use of standard horror moving picture props such as swirling smoke, safe bats, and cobwebs featured as gothic club décor from the beginning in The Batcave. Such references in bands' music and images were originally natural language-in-cheek, but every bit time went on, bands and members of the subculture took the connection more seriously. As a result, morbid, supernatural and occult themes became more noticeably serious in the subculture. The interconnection between horror and goth was highlighted in its early days past The Hunger, a 1983 vampire film starring David Bowie, Catherine Deneuve and Susan Sarandon. The moving picture featured gothic rock group Bauhaus performing Bela Lugosi's Expressionless in a nightclub. Tim Burton created a storybook temper filled with darkness and shadow in some of his films like Beetlejuice (1988), Batman (1989), Edward Scissorhands (1990), Batman Returns (1992) and the stop motility films The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), which was produced/co-written past Burton, and Corpse Bride (2005), which he co-produced. The Nickelodeon drawing Invader Zim is likewise based on the goth subculture.

As the subculture became well-established, the connectedness between goth and horror fiction became virtually a cliche, with goths quite probable to appear as characters in horror novels and film. For case, The Craft, The Crow, The Matrix and Underworld film series drew direct on goth music and style. The dark comedies Beetlejuice, The Kinesthesia, American Dazzler, Nuptials Crashers, and a few episodes of the blithe Television receiver bear witness S Park portray or parody the goth subculture. In S Park, several of the fictional schoolchildren are depicted every bit goths. The goth kids on the show are depicted as finding it annoying to be confused with the Hot Topic "vampire" kids from the episode "The Ungroundable" in season 12,[62] [63] and fifty-fifty more than frustrating to exist compared with emo kids. The goth kids are unremarkably depicted listening to goth music, writing or reading Gothic poetry, drinking coffee, flipping their hair, and smoking.[64] [65]

Morticia Addams from The Addams Family created by Charles Addams is a fictional grapheme and the mother in the Addams Family unit. Morticia was played by Carolyn Jones in the 1964 television show The Addams Family and by Anjelica Huston in the 1991 version, and voiced past Charlize Theron in 2019 animated motion picture.

Books and magazines [edit]

A prominent American literary influence on the gothic scene was provided by Anne Rice'due south re-imagining of the vampire in 1976. In The Vampire Chronicles, Rice'southward characters were depicted every bit self-tormentors who struggled with alienation, loneliness, and the human condition. Not simply did the characters torment themselves, only they too depicted a surreal world that focused on uncovering its splendour. These Chronicles assumed goth attitudes, but they were not intentionally created to represent the gothic subculture. Their romance, beauty, and erotic appeal attracted many goth readers, making her works popular from the 1980s through the 1990s.[66] While Goth has embraced Vampire literature both in its 19th century grade and in its later incarnations, Rice'south postmodern take on the vampire mythos has had a "special resonance" in the subculture. Her vampire novels feature intense emotions, menstruation clothing, and "cultured decadence". Her vampires are socially alienated monsters, merely they are too stunningly bonny. Rice's goth readers tend to envision themselves in much the aforementioned terms and view characters like Lestat de Lioncourt as role models.[27]

Richard Wright'due south novel Native Son contains gothic imagery and themes that demonstrate the links between blackness and the gothic; themes and images of "premonitions, curses, prophecies, spells, veils, demonic possessions, graves, skeletons" are nowadays, suggesting gothic influence.[67] Other classic themes of the gothic are present in the novel, such as transgression and unstable identities of race, class, gender, and nationality.[67]

The re-imagining of the vampire continued with the release of Poppy Z. Brite's book Lost Souls in October 1992. Despite the fact that Brite'southward first novel was criticized by some mainstream sources for allegedly "lack[ing] a moral center: neither terrifyingly malevolent supernatural creatures nor (like Anne Rice's protagonists) tortured souls torn between proficient and evil, these vampires just add blood-drinking to the amoral panoply of drug abuse, problem drinking and empty sexual practice good past their human being counterparts",[68] many of these so-called "human counterparts" identified with the teen angst and goth music references therein, keeping the book in print. Upon release of a special 10th anniversary edition of Lost Souls, Publishers Weekly—the same journal that criticized the novel'due south "amorality" a decade prior—deemed it a "modernistic horror archetype" and best-selling that Brite established a "cult audience".[69]

Neil Gaiman's graphic novel series The Sandman influenced goths with characters like the dark, brooding Dream and his sister, Death.[ citation needed ]

The 2002 release 21st Century Goth by Mick Mercer, an author, noted music journalist and leading historian of gothic stone,[70] [71] [72] explored the modern land of the goth scene around the world, including S America, Japan, and mainland Asia. His previous 1997 release, Hex Files: The Goth Bible, similarly took an international await at the subculture.

In the Usa, Propaganda was a gothic subculture magazine founded in 1982. In Italy, Ver Sacrum covers the Italian goth scene, including mode, sexuality, music, art and literature. Some magazines, such as the at present-defunct Dark Realms [73] and Goth Is Dead included goth fiction and poetry. Other magazines cover style (eastward.g., Gothic Beauty); music (e.g., Severance) or civilization and lifestyle (eastward.thousand., Althaus eastward-zine).

31 October 2011 ECW Press published the Encyclopedia Gothica [74] written by author and poet Liisa Ladouceur with illustrations done by Gary Pullin.[75] [76] [77] [78] This non-fiction book describes over 600 words and phrases relevant to Goth subculture.

Brian Craddock'southward 2017 novel Eucalyptus Goth[79] charts a year in the life of a household of twenty-somethings in Brisbane, Australia. The central characters are deeply entrenched in the local gothic subculture, with the book exploring themes relevant to the characters, notably unemployment, mental health, politics, and relationships.[80]

Graphic fine art [edit]

Visual contemporary graphic artists with this aesthetic include Gerald Brom, Dave McKean, and Trevor Brown as well as illustrators Edward Gorey, Charles Addams, Lorin Morgan-Richards, and James O'Barr. The artwork of Shine surrealist painter Zdzisław Beksiński is ofttimes described as gothic.[81] British artist Anne Sudworth published a book on gothic art in 2007.[82]

Events [edit]

There are large annual goth-themed festivals in Deutschland, including Wave-Gotik-Treffen in Leipzig and M'era Luna in Hildesheim), both annually attracting tens of thousands of people. Castle Party is the biggest goth festival in Poland.[83]

Interior design [edit]

In the 1980s, goths decorated their walls and ceilings with black fabrics and accessories like rosaries, crosses and plastic roses. Black article of furniture and cemetery-related objects such as candlesticks, death lanterns and skulls were too part of their interior blueprint. In the 1990s, the interior design arroyo of the 1980s was replaced by a less macabre style.[84]

Sociology [edit]

Gender and sexuality [edit]

Since the late 1970s, the UK goth scene refused "traditional standards of sexual propriety" and accepted and historic "unusual, bizarre or deviant sexual practices".[85] In the 2000s, many members "... claim overlapping memberships in the queer, polyamorous, bondage-subject/sadomasochism, and pagan communities".[86]

Though sexual empowerment is not unique to women in the goth scene, it remains an important part of many goth women'due south experience: The "... [southward]cene's celebration of active sexuality" enables goth women "... to resist mainstream notions of passive femininity". They take an "active sexuality" approach which creates "gender egalitarianism" within the scene, as information technology "allows them to appoint in sexual play with multiple partners while sidestepping virtually of the stigma and dangers that women who engage in such beliefs" exterior the scene often incur, while continuing to "... see themselves every bit strong".[87]

Men dress up in an androgynous style: "... Men 'gender blend,' wearing makeup and skirts". In contrast, the "... women are dressed in sexy feminine outfits" that are "... highly sexualized" and which often combine "... corsets with short skirts and fishnet stockings". Androgyny is mutual among the scene: "... androgyny in Goth subcultural way often disguises or fifty-fifty functions to reinforce conventional gender roles". Information technology was only "valorised" for male person goths, who adopt a "feminine" appearance, including "make-up, skirts and feminine accessories" to "heighten masculinity" and facilitate traditional heterosexual courting roles.[88]

Identity [edit]

While goth is a music-based scene, the goth subculture is besides characterised by particular aesthetics, outlooks, and a "manner of seeing and of being seen". The last years, through social media, goths are able to meet people with similar interests, learn from each other, and finally, to take part in the scene. These activities on social media are the manifestation of the same practices which are taking identify in goth clubs.[89] This is non a new miracle since before the rise of social media on-line forums had the same function for goths.[90] Observers have raised the result of to what degree individuals are truly members of the goth subculture. On one end of the spectrum is the "Uber goth", a person who is described as seeking a pallor so much that he or she applies "... as much white foundation and white powder every bit possible".[91] On the other end of the spectrum another writer terms "poseurs": "goth wannabes, normally immature kids going through a goth phase who do not hold to goth sensibilities only desire to be part of the goth crowd..".[92] Information technology has been said that a "mallgoth" is a teen who dresses in a goth style and spends fourth dimension in malls with a Hot Topic store, but who does not know much virtually the goth subculture or its music, thus making him or her a poseur.[93] In 1 instance, fifty-fifty a well-known performer has been labelled with the pejorative term: a "number of goths, particularly those who belonged to this subculture earlier the late-1980s, decline Marilyn Manson as a poseur who undermines the true meaning of goth".[94]

Media and bookish commentary [edit]

The BBC described bookish research that indicated that goths are "refined and sensitive, corking on poetry and books, non large on drugs or anti-social behaviour".[95] Teens frequently stay in the subculture "into their adult life", and they are probable to become well-educated and enter professions such as medicine or law.[95] The subculture carries on appealing to teenagers who are looking for significant and for identity. The scene teaches teens that there are difficult aspects to life that y'all "have to make an endeavour to understand" or explain.[96]

The Guardian reported that a "mucilage bounden the [goth] scene together was drug use"; nonetheless, in the scene, drug utilise was varied. Goth is ane of the few subculture movements that is not associated with a single drug,[32] in the way that the Hippie subculture is associated with cannabis and the Modern subculture is associated with amphetamines. A 2006 study of young goths found that those with higher levels of goth identification had higher drug use.[97]

Perception on nonviolence [edit]

A study conducted by the Academy of Glasgow, involving 1,258 youth interviewed at ages 11, 13, 15 and 19, plant goth subculture to be strongly nonviolent and tolerant, thus providing "valuable social and emotional support" to teens vulnerable to cocky harm and mental illness.[98]

School shootings [edit]

In the weeks post-obit the 1999 Columbine High School massacre, media reports nigh the teen gunmen, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, portrayed them as part of a gothic cult. An increased suspicion of goth subculture later on manifested in the media.[99] This led to a moral panic over teen interest in goth subculture and a number of other activities, such as violent video games.[100] Harris and Klebold had initially been thought to be members of "The Trenchcoat Mafia"; an informal society inside Columbine High School. Later, such characterizations were considered wrong.[101]

Media reported that the gunman in the 2006 Dawson College shooting in Montreal, Quebec, Kimveer Singh Gill, was interested in goth subculture.[102] Gill's self-professed love of Goth culture was the topic of media involvement, and it was widely reported that the discussion "Goth", in Gill's writings, was a reference to the alternative industrial and goth subculture rather than a reference to gothic stone music.[102] Gill, who committed suicide after the attack, wrote in his online journal: "I'thou so sick of hearing well-nigh jocks and preps making life difficult for the goths and others who wait unlike, or are different".[103] Gill described himself in his contour on Vampirefreaks.com every bit "... Trench ... the Angel of Death" and he stated that "Metallic and Goth boot ass".[104] An paradigm gallery on Gill's Vampirefreaks.com web log had photos of him pointing a gun at the camera or wearing a long black trench coat.[105]

Mick Mercer stated that Gill was "not a Goth. Never a Goth. The bands he listed equally his chosen grade of ear-bashing were relentlessly metal and standard grunge, rock and goth metal, with some industrial presence". Mercer stated that "Kimveer Gill listened to metal", "He had cypher whatsoever to do with Goth" and further commented "I realise that similar many Neos [neophyte], Kimveer Gill may even have believed he somehow was a Goth, because they're [Neophytes] simply really noted for spectacularly missing the betoken".[106]

Prejudice and violence directed at goths [edit]

In part because of public misunderstanding surrounding gothic aesthetics, people in the goth subculture sometimes suffer prejudice, discrimination, and intolerance. Equally is the case with members of various other subcultures and culling lifestyles, outsiders sometimes marginalize goths, either by intention or by blow.[107] Actress Christina Hendricks talked of being bullied every bit a goth at school and how difficult information technology was for her to bargain with societal pressure: "Kids tin be pretty judgmental nigh people who are different. But instead of breaking down and conforming, I stood house. That is also probably why I was unhappy. My mother was mortified and kept telling me how horrible and ugly I looked. Strangers would walk past with a look of daze on their face, so I never felt pretty. I merely always felt awkward".[108]

On 11 August 2007, a couple walking through Stubbylee Park in Bacup (Lancashire) were attacked by a grouping of teenagers because they were goths. Sophie Lancaster subsequently died from her injuries.[109] On 29 Apr 2008, two teens, Ryan Herbert and Brendan Harris, were bedevilled for the murder of Lancaster and given life sentences; three others were given bottom sentences for the assault on her boyfriend Robert Maltby. In delivering the judgement, Judge Anthony Russell stated, "This was a hate criminal offence against these completely harmless people targeted because their appearance was different to yours". He went on to defend the goth community, calling goths "perfectly peaceful, law-abiding people who pose no threat to anybody".[110] [111] Approximate Russell added that he "recognised it as a hate crime without Parliament having to tell him to do so and had included that view in his sentencing".[112] Despite this ruling, a pecker to add discrimination based on subculture affiliation to the definition of detest crime in British law was non presented to parliament.[113]

In 2013, law in Manchester appear they would be treating attacks on members of culling subcultures, such equally goths, the same every bit they do for attacks based on race, religion, and sexual orientation.[114]

A more than recent phenomenon is that of goth YouTubers who very often address the prejudice and violence confronting goths. They create videos as a response to bug that they personally face, which include challenges such every bit bullying, and dealing with negative descriptions of themselves. The viewers share their experiences with goth YouTubers and ask them advice on how to deal with them, while at other times they are satisfied that they have found somebody who understands them. Ofttimes, goth YouTubers personally reply to their viewers with personal messages or videos. These interactions accept the form of an informal mentoring which contributes to the building of solidarity within the goth scene. This informal mentoring becomes central to the integration of new goths into the scene, into learning about the scene itself, and furthermore, as an assist to coping with problems that they confront.[89]

Cocky-harm study [edit]

A written report published on the British Medical Journal ended that "identification as belonging to the Goth subculture [at some point in their lives] was the best predictor of cocky harm and attempted suicide [among young teens]", and that information technology was virtually perhaps due to a selection machinery (persons that wanted to harm themselves later identified equally goths, thus raising the percentage of those persons who identify as goths).[97]

Co-ordinate to The Guardian, some goth teens are more likely to harm themselves or endeavour suicide. A medical journal study of i,300 Scottish schoolchildren until their teen years found that the 53% of the goth teens had attempted to harm themselves and 47% had attempted suicide. The written report found that the "correlation was stronger than whatever other predictor".[115] The study was based on a sample of xv teenagers who identified as goths, of which 8 had self-harmed by any method, 7 had cocky-harmed by cutting, scratching or scoring, and 7 had attempted suicide.[116]

The authors held that most self-harm past teens was washed earlier joining the subculture, and that joining the subculture would actually protect them and assist them deal with distress in their lives.[116] [117] The researchers cautioned that the report was based on a small sample size and needed replication to confirm the results.[116] [117] The written report was criticized for using simply a small-scale sample of goth teens and not taking into account other influences and differences between types of goths.[118] [119] [97]

See also [edit]

- Night academia

- Visual kei

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Nym, Alexander: Schillerndes Dunkel. Geschichte, Entwicklung und Themen der Gothic-Szene, Plöttner Verlag 2010, ISBN iii-862-11006-0, pp. 145−169

- ^ Farin, Klaus; Wallraff, Kirsten; Archiv der Jugendkulturen e.5., Berlin (1999). Die Gothics: Interviews, Fotografien (Orig.-Ausg. ed.). Bad Tölz: Tilsner. p. 23. ISBN9783933773098.

- ^ John Stickney (24 October 1967). "Four Doors to the Future: Gothic Rock Is Their Affair". The Williams Record. Posted at "The Doors : Articles & Reviews Year 1967". Mildequator.com. Archived from the original on 4 May 2013. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

"The Doors are not pleasant, agreeable hippies proffering a grin and a flower; they wield a knife with a cold and terrifying edge. The Doors are closely akin to the national sense of taste for violence, and the power of their music forces each listener to realize what violence is in himself".... "The Doors met New York for better or for worse at a press conference in the gloomy vaulted vino cellar of the Delmonico hotel, the perfect room to accolade the Gothic rock of the Doors".

- ^ Loder, Kurt (December 1984). V.U. (album liner notes). Verve Records.

- ^ Kent, Nick (29 July 1978). "Banshees brand the Breakthrough alive review - London the Roundhouse 23 July 1978". NME.

- ^ Kent, Nick (31 March 1979). "Magazine's Mad Minstrels Gains Momentum (Album review)". NME. p. 31.

- ^ "Something Else [featuring Joy Division]". BBC television [archive added on youtube]. 15 September 1979. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021.

Because it is unsettling, it is like sinister and gothic, information technology won't be played. [interview of Joy Division'south manager Tony Wilson next to Joy Division's drummer Stephen Morris from 3:31]

- ^ Reynolds 2005, p. 352.

- ^ a b Reynolds 2005, p. 432.

- ^ Des Moines (26 Oct 1979). "Live review past Des Moines (Joy Division Leeds)". Sounds.

Curtis may project similar an ambidextrous barman puging his physical hang-ups, only the 'Gothic dance music' he orchestrates is well-understood by those who recognise their New Wave frontiersmen and know how to trip the light fantastic the Joy Division! A theatrical sense of timing, controlled improvisation...

- ^ Bohn, Chris. "Northern gloom: 2 Southern stomp: 1. (Joy Division: University of London Union – Live Review)". Melody Maker (16 February 1980).

Joy Division are masters of this Gothic gloom

- ^ Fell, Jon (July 1994). "Joy Sectionalisation: Someone Take These Dreams Away". Mojo via Rock'southward Backpages (subscription required) . Retrieved ten July 2014.

a definitive Northern Gothic statement: guilt-ridden, romantic, claustrophobic

- ^ a b Keaton, Steve (21 February 1981). "The Face of Punk Gothique". Sounds.

- ^ Spracklen, Karl; Spracklen, Beverley (2018). The Evolution of Goth Culture: The Origins and Deeds of the New Goths. Emerald Publishing. p. 46.

The F-Club and the Futurama festival, both set up and run by Leeds promoter, John Keenan, have get entrenched in the shared memory of mail service-punks and goths as spaces where goth rock was born in the grade it is now known.

Stewart, Ethan (13 January 2021). "How Leeds Led Goth". PopMatters . Retrieved 3 June 2021.

Deboick, Sophia (17 September 2020). "A City in Music - Leeds: Goth ground zero". The New European. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021. - ^ Johnson, David (February 1983). "69 Dean Street: The Making of Club Civilization". The Face. No. 34. p. 26. Retrieved seven Apr 2018.

- ^ North, Richard (19 February 1983). "Punk Warriors". NME.

- ^ Ohanesian, Liz (4 November 2009). "The LA Deathrock Starter Guide". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on fourteen July 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ^ Reynolds 2005, p. 429.

- ^ Reynolds 2005, p. 421.

- ^ Mason, Stewart. "Pornography – The Cure : Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards : AllMusic". AllMusic . Retrieved 27 Oct 2012.

- ^ Reynolds 2005, p. 431.

- ^ Reynolds 2005, p. 435.

- ^ Rambali, Paul. "A Rare Glimpse into A Private World". The Face (July 1983).

Curtis' expiry wrapped an already mysterious group in legend. From the press eulogies, you would call back Curtis had gone to bring together Chatterton, Rimbaud and Morrison in the hallowed hall of premature harvests. To a grouping with several strong Gothic characteristics was added a further piece of romance.

- ^ Houghton, Jayne (June 1984). "Crime Pays!". ZigZag. p. 21.

- ^ a b Simpson, Dave (29 September 2006). "Back in black: Goth has risen from the dead - and the 1980s pioneers are (naturally) not happy virtually it". The Guardian . Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ Klosterman, Chuck (June 2003), "Who: Marilyn Manson", Spin

- ^ a b c d e f Goodlad & Bibby 2007.

- ^ Richter & 1987. sfn error: no target: CITEREFRichter1987. (assistance)

- ^ Koszarski 1994, p. 140.

- ^ "The American Film Institute, catalog of motility pictures, Volume 1, Part 1, Characteristic films 1941-1950, The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr Toad"

- ^ Roger Ebert (19 November 1999). "Sleepy Hollow". Chicago Dominicus-Times . Retrieved i November 2010.

- ^ a b c Simpson, Dave (29 September 2006). "Back in black: Goth has risen from the dead - and the 1980s pioneers are (naturally) non happy nigh it". The Guardian . Retrieved fourteen July 2014. "Severin admits his ring (Siouxsie and the Banshees) pored over gothic literature - Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Baudelaire".

- ^ Goodlad & Bibby 2007, p. xiv.

- ^ Kilpatrick 2004, p. 210.

- ^ Spuybroek 2011, p. 42.

- ^ Kilpatrick 2004, p. 88.

- ^ Noel Fielding: rocking a new await. The Guardian. Author - Simon Hattenstone. Published i Feb 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2017.

- ^ Johnson, David (i February 1983). "69 Dean Street: The Making of Gild Culture". The Face up (effect 34, page 26, republished at Shapersofthe80s.com) . Retrieved seven April 2018.

- ^ Harriman, Andi; Bontje, Marloes: Some Wear Leather, Some Wear Lace. The Worldwide Compendium of Post Punk and Goth in the 1980s, Intellect Books 2014, ISBN one-783-20352-8, p. 66

- ^ Stevens, Jenny (15 Feb 2013). "Button The Sky Abroad". NME . Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ Hannaham 1997, p. 93 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHannaham1997 (assist)

- ^ a b Steele & Park 2008, p. 26 harvnb fault: no target: CITEREFSteelePark2008 (help)

- ^ a b Steele & Park 2008, p. 35 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSteelePark2008 (help)

- ^ Reynolds, p. 425.

- ^ Hannaham 1997, p. 113 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHannaham1997 (assistance)

- ^ Steele & Park 2008, p. eighteen harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSteelePark2008 (assist)

- ^ a b c d eastward Grunenberg 1997, p. 172 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFGrunenberg1997 (help)

- ^ Steele & Park 2008, p. 38 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSteelePark2008 (assistance)

- ^ Holiday, Steven (12 Dec 2014). "Gothic Dazzler". Portland, OR: Holiday Media. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ a b c La Ferla, Ruth (thirty October 2005). "Encompass the Darkness". The New York Times . Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ Eric Lipton Disturbed Shooters Weren't True Goth from the Chicago Tribune, 27 April 1999

- ^ Polhemus, Ted (1994). Street Style. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 97. Cited in Mellins 2013, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Aurelio Voltaire Hernandez: What Is Goth?, Publishers Group UK, ISBN 1-578-63322-2

"Serene, thoughtful and creative, ethergoths are defined by their affinity ... darkwave and classically inspired Gothic music. Ethergoths are more probable to exist plant sipping tea, writing poetry and listening to the Cocteau Twins than jumping upwards and downwards at a club." - ^ a b c d e f m Wilson, Cintra (17 September 2008). "You just tin't impale it". The New York Times . Retrieved eighteen September 2008.

- ^ a b c Grunenberg 1997, p. 173 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFGrunenberg1997 (assistance)

- ^ a b c d e Steele & Park 2008, p. 3 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFSteelePark2008 (aid)

- ^ Bolton, Andrew (2013). Anna Sui. New York: Relate Books. pp. 100–109. ISBN978-1452128597 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b La Ferla, Ruth: "Comprehend the Darkness". New York Times, 30 October 2005. [one]

- ^ Johanna Lenander, "Swede and Sour: Scandinavian Goth," New York Times: T Magazine, 27 March 2009. [2] Access appointment: 29 March 2009.

- ^ Nancy Kilpatrick. Goth Bible: A Compendium for the Darkly Inclined. St. Martin's Griffin, 2004, p. 24

- ^ Ladouceur 2011, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Modell, Josh (xix November 2008). "The Ungroundable". The A.V. Social club.

- ^ Fickett, Travis (20 November 2008). "IGN: The Ungroundable Review". IGN. News Corporation. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- ^ Modell, Josh (xix November 2008). "The Ungroundable". The A.V. Lodge . Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ^ "FAQ Archives: Why aren't the goth kids in the class w/ the rest of the kids when they show them all at their desk?". Due south Park Studios. half dozen May 2004. Archived from the original on half dozen March 2009. Retrieved 23 Nov 2008.

- ^ Jones 2015, pp. 179–204.

- ^ a b Smethurst, James (Spring 2001). "Invented by Horror: The Gothic and African American Literary Credo in Native Son". African American Review. 35 (i): 29–30. doi:10.2307/2903332. JSTOR 2903332.

- ^ "Fiction Book Review: Lost Souls past Poppy Z. Brite". publishersweekly.com. 31 August 1992. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ "Fiction review: The American Fantasy Tradition by Brian Yard. Thomsen". publishersweekly.com. 1 September 2002. Retrieved eighteen March 2012.

- ^ Blu Interview with Mick Mercer Starvox.internet

- ^ Kyshah Hell Interview with Mick Mercer Morbidoutlook.com

- ^ Mick Mercer Archived ix April 2007 at the Wayback Machine Broken Ankle Books

- ^ Night Realms

- ^ Liisa., Ladouceur (2011). Encyclopedia Gothica. Pullin, Gary. Toronto: ECW Press. ISBN978-1770410244. OCLC 707327955.

- ^ "Book Review: Encyclopedia Gothica, past Liisa Ladouceur". National Post. eleven November 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ Rouner, Jef (28 October 2011). "Encyclopedia Gothica: Liisa Ladouceur Explains It All". Houston Press. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved seven March 2018.

- ^ "Book Review: 'Encyclopedia Gothica' - Liisa Ladouceur - Terrorizer". Terrorizer. 3 January 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ "REVIEW: Encyclopedia Gothica - Macleans.ca". Macleans.ca. 2 Nov 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ Goodreads Eucalyptus Goth

- ^ Renae Holyoak A Dearest Alphabetic character to Brisbane Outback Revue

- ^ "The Cursed Paintings of Zdzisław Beksiński". Culture.pl . Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Sudworth 2007.

- ^ "Festival Website".

- ^ "Gothic room furnishings".

- ^ Siegel 2007, p. 350.

- ^ Wilkins 2004.

- ^ Wilkins 2004, p. 329.

- ^ Spooner, Catherine (28 May 2009). "Goth Culture: Gender, Sexuality and Style". Times Higher Education . Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ a b Karampampas, Panas (13 September 2020). "Goth YouTubers and the informal mentoring of young goths: peer support and solidarity in the Greek goth scene". Journal of Youth Studies. 23 (8): 989–1003. doi:10.1080/13676261.2019.1646892. ISSN 1367-6261. S2CID 200084598.

- ^ Hodkinson, Paul (2002). Goth: Identity, Way and Subculture. Berg Publishers. doi:10.2752/9781847888747/goth0012. ISBN978-i-84788-874-7.

- ^ Goodlad & Bibby 2007, p. 36.

- ^ Kilpatrick 2004, p. 24.

- ^ Ladouceur 2011.

- ^ Siegel 2007, p. 344.

- ^ a b Winterman, Denise. "Upwards gothic". BBC News Mag.

- ^ Morgan, Fiona (16 December 1998). "The devil in your family unit room". Salon . Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ a b c Immature, Sweeting & West 2006.

- ^ "Goth subculture may protect vulnerable children". New Scientist. 14 April 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ^ Goldberg, Carey (one May 1999). "For Those Who Dress Differently, an Increment in Beingness Viewed as Aberrant". The New York Times . Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ Janelle Brown (23 Apr 1999). "Doom, Quake and mass murder". Salon. Archived from the original on nineteen September 2008. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

- ^ Cullen, Dave (23 September 1999). "Inside the Columbine High investigation". Salon . Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ a b fourteen September 2006. Shooting past Canadian trench coat killer affects industrial / goth scene Archived xix February 2013 at the Wayback Machine Side-line.com. Retrieved on 13 March 2007.

- ^ "Chronologie d'un folie (Kimveer'south online Journal)". La Presse. 15 September 2006. Archived from the original on 11 Oct 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ^ CBC News: Montreal gunman called himself 'affections of death'

- ^ canada.com Archived 12 March 2007 at the Wayback Auto

- ^ Mick Mercer Mick Mercer talks near Kimveer Gill [ permanent dead link ] mickmercer.livejournal.com

- ^ Goldberg, Carey (1 May 1999). "Terror in Littleton: The Shunned; For Those Who Clothes Differently, an Increase in Beingness Viewed as Abnormal". The New York Times . Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ "Christina Hendricks: 'I was bullied at school for being a goth'". Archived from the original on xi January 2022.

- ^ "Goth couple badly hurt in attack". BBC News-United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland. 11 August 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Byrne, Paul (29 April 2008). "Life jail trms for teenage thugs who killed goth girl". dailyrecord.co.uk . Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Pilling, Kim (29 April 2008). "Ii teenagers sentenced to life over murder of Goth". Contained.co.uk. Archived from the original on v August 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Henfield, Sally (29 April 2008). "Sophie's family and friends vow to carry on campaign". lancashiretelegraph.co.uk . Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Smyth, Catherine (4 April 2008). "Call for detest crimes law change". manchestereveningnews.co.britain . Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ "Manchester goths become constabulary protection". 3 News NZ. 5 April 2013. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015.

- ^ Polly Curtis and John Carvel. "Teen goths more prone to suicide, report shows". The Guardian, Friday xiv April 2006

- ^ a b c "Goths 'more than probable to cocky-harm'". BBC. xiii April 2006. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ a b Gaia Vince (14 Apr 2006). "Goth subculture may protect vulnerable children". New Scientist . Retrieved xviii March 2012.

- ^ Taubert, Mark; Kandasamy, Jothy (2006). "Cocky Harm in Goth Youth Subculture: Decision Relates Just to Pocket-sized Sample". BMJ (letter to the editor). 332 (7551): 1216. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7551.1216. PMC1463972. PMID 16710018.

- ^ Phillipov, Michelle (2006). "Self Damage in Goth Youth Subculture: Report Merely Reinforces Popular Stereotypes". BMJ (letter to the editor). 332 (7551): 1215–1216. doi:ten.1136/bmj.332.7551.1215-b. PMC1463947. PMID 16710012.

Bibliography [edit]

- Goodlad, Lauren One thousand. Eastward.; Bibby, Michael (2007). "Introduction". In Goodlad, Lauren Thousand. E.; Bibby, Michael (eds.). Goth: Undead Subculture. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Printing. pp. i–37. ISBN978-0-8223-8970-v.

- Jones, Timothy (2015). The Gothic and the Gothic Carnivalesque in American Culture. Cardiff, Wales: University of Wales Press. ISBN978-i-78316-230-7. JSTOR j.ctt17w8hdq.

- Kilpatrick, Nancy (2004). Goth Bible: A Compendium for the Darkly Inclined. New York: St. Martin'southward Griffin. ISBN978-0-312-30696-0.

- Koszarski, Richard (1994). An Evening's Entertainment: The Historic period of the Silent Feature Picture, 1915–1928. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN978-0-520-08535-0.

- Ladouceur, Liisa (2011). Encyclopedia Gothica. Illustrated by Pullin, Gary. Toronto: ECW Printing.

- Mellins, Maria (2013). Vampire Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN978-1-4725-0385-five.

- Pokhrel, Pallav; Sussman, Steven; Blackness, David; Sunday, Ping (2010). "Peer Grouping Self-Identification equally a Predictor of Relational and Physical Assailment Among Loftier School Students". Journal of School Wellness. 80 (5): 249–258. doi:x.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00498.x. PMC3134410. PMID 20529198.

- Reynolds, Simon (2005). Rip It Up and Get-go Again: Postpunk 1978–1984. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN978-0-571-21569-0.

- Richter, David H. (1987). "Gothic Fantasia: The Monsters and The Myths: A Review-Article". The Eighteenth Century. 28 (2): 149–170. ISSN 0193-5380. JSTOR 41467717.

- Rutledge, Carolyn Chiliad.; Rimer, Don; Scott, Micah (2008). "Vulnerable Goth Teens: The Part of Schools in This Psychosocial High-Risk Culture". Periodical of School Health. 78 (9): 459–464. doi:ten.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00331.10. ISSN 1746-1561. PMID 18786038.

- Siegel, Carol (2007). "That Obscure Object of Desire Revisited: Poppy Z. Brite and the Goth Hero equally Masochist". In Goodlad, Lauren M. E.; Bibby, Michael (eds.). Goth: Undead Subculture. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. pp. 335–356. ISBN978-0-8223-8970-5.

- Spuybroek, Lars (2011). The Sympathy of Things: Ruskin and the Environmental of Design. Rotterdam, Netherlands: V2_Publishing. ISBN978-90-5662-827-7.

- Sudworth, Anne (2007). Gothic Fantasies: The Paintings of Anne Sudworth. London: AAPPL Artists' and Photographers' Printing. ISBN978-1-904332-56-5.

- Wilkins, Amy C. (2004). "'So Total of Myself as a Chick': Goth Women, Sexual Independence, and Gender Egalitarianism" (PDF). Gender & Lodge. viii (iii): 328–349. CiteSeerX10.i.1.413.9162. doi:10.1177/0891243204264421. ISSN 0891-2432. JSTOR 4149405. S2CID 11244993.

- Young, Robert; Sweeting, Helen; Due west, Patrick (2006). "Prevalence of Deliberate Self Harm and Attempted Suicide inside Contemporary Goth Youth Subculture: Longitudinal Cohort Study". BMJ. 332 (7549): 1058–1061. doi:ten.1136/bmj.38790.495544.7C. ISSN 1756-1833. PMC1458563. PMID 16613936.

Farther reading [edit]

- Baddeley, Gavin (2002). Goth Chichi: A Connoisseur's Guide to Night Civilisation. Plexus. ISBN978-0-85965-308-4.

- Brill, Dunja (2008). Goth Civilisation: Gender, Sexuality and Mode. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

- Catalyst, Clint (2000). Cottonmouth Kisses. San Francisco, California: Manic D Press. ISBN978-0-916397-65-4.

A first-person account of an individual'southward life within the Goth subculture. - Davenport-Hines, Richard (1999). Gothic: 4 Hundred Years of Excess, Horror, Evil and Ruin . New York: North Port Press. ISBN978-0-86547-590-8.

A chronological/aesthetic history of Goth covering the spectrum from Gothic architecture to the Cure. - Digitalis, Raven (2007). Goth Craft: The Magickal Side of Dark Culture. Woodbury, Minnesota: Llewellyn Publications. ISBN978-0-7387-1104-1.

Includes a lengthy explanation of Gothic history, music, fashion, and proposes a link between mystic/magical spirituality and dark subcultures. - Fuentes Rodríguez, César (2007). Mundo Gótico (in Castilian). Quarentena Ediciones. ISBN978-84-933891-6-1.

Covering literature, music, cinema, BDSM, fashion, and subculture topics. - Hodkinson, Paul (2002). Goth: Identity, Fashion and Subculture. Oxford: Berg Publishers. ISBN978-one-85973-600-5.

- ——— (2005). "Communicating Goth: On-line Media". In Gelder, Ken (ed.). The Subcultures Reader (2d ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 567–574. ISBN978-0-415-34416-6.

- Mercer, Mick (1996). Hex Files: The Goth Bible. London: Batsford. ISBN978-0-7134-8033-7.

An international survey of the Goth scene. - ——— (2002). 21st Century Goth. London: Reynolds & Hearn. ISBN978-1-903111-28-iv.

An exploration of the mod country of the Goth subculture worldwide. - Scharf, Natasha (2011). Worldwide Gothic: A Chronicle of a Tribe. Church Stretton, England: Independent Music Press. ISBN978-one-906191-19-ane.

A global view of the goth scene from its birth in the belatedly 1970s to the present day. - Vas, Abdul (2012). For Those About to Ability. Madrid: T.F. Editores. ISBN978-84-15253-52-v.

- Venters, Jillian (2009). Gothic Charm School: An Essential Guide for Goths and Those Who Love Them. Illustrated past Venters, Pete. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN978-0-06-166916-3.

An etiquette guide to "gently persuade others in her chosen subculture that existence a polite Goth is much, much more subversive than just wearing T-shirts with "edgy" sayings on them". - Voltaire (2004). What is Goth?. Boston: Weiser Books. ISBN978-i-57863-322-7.

An illustrated view of the goth subculture.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goth_subculture

0 Response to "What Kind of Jewelry Clothes and Art Work Do Christian Goths Use"

Post a Comment